3. Bodies in Spaces

(2023)

This is an extract of an article that appears in full in Journal of Illustration Research, Volume 9, Numbers 1&2, 2023, pp. 15-29. The article was based on a keynote presentation given at Education and Illustration: Models Methods Paradigms a virtual conference held by Kingston University (London) in 2021

This article is (hopefully) the beginning of ideas about the discipline of ‘illustration’ as it is bounded by and created for higher education. It is not quite an academic article and more a series of starting points for a series of further articles. Thinking about the broad concept of bodies in spaces was a useful entry point for considering both pedagogy and illustration as a whole. The way we are as bodies and the way bodies are depicted are two very important concerns for illustration. I have based my thinking on my experiences teaching in a wide range of institutions in the United Kingdom and in the United States (at Parsons School of Design). I intend to spend the next few years filling in some of the gaps of this research by attempting to map illustration as it is taught and discussed in higher education and the work that can be done to dismantle and decolonize this ‘illustration’ and to begin to think about an alternative illustration that evades the forms of knowing currently facilitated within the university.

COVID-19 has reminded us that universities are collections of bodies in spaces, something that many of our university experiences aim to obfuscate or avoid. As bell hooks writes, ‘I have witnessed a grave sense of dis-ease among professors (irrespective of their politics) when students want to see them as whole human beings with complex lives and experiences rather than seekers after compartmentalized bits of knowledge’ (hooks 1994: 15).

Universities are spaces where knowledge is compartmentalized conceptually, through disciplines and spatially, through the organization of the buildings. COVID-19 crossed the boundaries of both. The reminder that we might infect one another is a reminder that we occupy academic spaces together as bodies; bodies that might fail. Our bodies are not bounded or discreet and the virus demonstrates how any hierarchies or walls between disciplines or people are imagined. University staff who are made invisible by the process of learning, by which I mean that they are not commonly thought to factor into it at all; the cleaners, security guards, canteen staff and maintenance people are just as present as bodies and sources of knowledge in the spaces of the university as the students and faculty. COVID had the dual role of initially increasing our awareness of all of the bodies that were part of our community and then when lockdown began, erasing non-academic staff entirely. It is interesting that many of the people not considered part of our learning are in fact caring for either our bodies, the buildings that contain them or both. The pandemic forced our bodies and the bodies of those around us into the foreground (both figuratively and literally via Zoom), something that we now seem to be trying to forget.

Universities are spaces where knowledge is compartmentalized conceptually, through disciplines and spatially, through the organization of the buildings. COVID-19 crossed the boundaries of both. The reminder that we might infect one another is a reminder that we occupy academic spaces together as bodies; bodies that might fail. Our bodies are not bounded or discreet and the virus demonstrates how any hierarchies or walls between disciplines or people are imagined. University staff who are made invisible by the process of learning, by which I mean that they are not commonly thought to factor into it at all; the cleaners, security guards, canteen staff and maintenance people are just as present as bodies and sources of knowledge in the spaces of the university as the students and faculty. COVID had the dual role of initially increasing our awareness of all of the bodies that were part of our community and then when lockdown began, erasing non-academic staff entirely. It is interesting that many of the people not considered part of our learning are in fact caring for either our bodies, the buildings that contain them or both. The pandemic forced our bodies and the bodies of those around us into the foreground (both figuratively and literally via Zoom), something that we now seem to be trying to forget. The space the university occupies

The space the university occupiesClassrooms are containers for both bodies and knowledge. They keep sound in, they reflect academic organization and hierarchies and they also occupy spaces in buildings. In A Third University Is Possible la paperson writes that ‘[u] niversities do not exist in some abstract academic place. They are built on land, and especially in a North American context, upon occupied Indigenous lands’ (2017: 25). In the United States universities are occupying stolen territory and so their presence is colonizing both physically and academically. In their article ‘Decolonization is not a metaphor’, Tuck and Yang talk about the problem of pursuing a decolonizing curriculum in universities that embody colonialism,

At a conference on educational research, it is not uncommon to hear speakers refer, almost casually, to the need to ‘decolonize our schools,’ or use ‘decolonizing methods,’ or ‘decolonize student thinking.’ Yet, we have observed a startling number of these discussions make no mention of Indigenous peoples, our/their struggles for the recognition of our/their sovereignty, or the contributions of Indigenous intellectuals and activists to theories and frameworks of decolonization.

(2012: 2)

What Tuck and Yang are describing is decolonization (in the United States) as a physical movement of bodies. In the United Kingdom, this might look like a decolonized curriculum being developed in a university that is not openly discussing (and making reparations for) its relationship with colonialism (which in some cases may has more or less directly paid for the university’s buildings) and the way that colonial relationships are playing out in its employment of non-academic staff. ‘When we are taught that we cannot know things unless we are taught by great minds, we submit to a whole suite of unfree practices that take on the form of a colonial relation (Freire in Halberstam 2011: 14).

Buildings as containers of learning

The buildings that compose the university are systems for organizing thought. Spaces in universities are parcelled out in ways that indicate the value placed on the activities they will hold. At a very basic level this is demonstrated by the ways that lecture theatres are structured to imply a certain kind of learning (one person at the front delivering knowledge, many people listening). In her essay on the role of domestic workers in Brazil, Livia Barbosa calls this imposition of hierarchy within architecture, a building’s ‘symbolic cartography’ (2012: 27). University spaces dictate the flow of knowledge. Many institutions are using the shared spaces of atria to explicitly outline their educational philosophy. Grafton architects who designed the townhouse building at Kingston University describe the building as follows:

The educational vision and ethos of this building is uniquely rich and progressive. Unexpected adjacencies are set up by virtue of the programme given to us by the University. The library facility is twinned with dance studios, performance and event spaces. The building is a democratic open infrastructure, a labyrinth of interlocking volumes, maintaining the feeling of being in one unified environment where these opposites can happily coexist.

(Grafton Architects n.d.: n.pag.)

This description is ideological, it is an expression of a vision of a type of fluid, unbounded learning, that has a permeability with the city spaces it inhabits. This vision of permeability was nightmarishly realized by COVID. Spaces of knowledge moved out of campuses and into homes exposing many students to the danger or precarity of a newly porous space of learning but also disrupting academic hierarchies in a way that these buildings often fail to achieve. Norman Foster, chair of the 2021 RIBA Stirling Prize jury, described the townhouse as ‘a theatre for life – a warehouse of ideas’ (Wainright 2021: n.pag.). The educational philosophy of the university is both being made explicit by and demonstrated by the space it contains. The vision is a display of dynamic and active bodies whose engagement in learning can be made visible. There is a presumption (born in privilege) that it is always safe and desirable to have learning made visible.

There are numerous examples of this type of educational architecture, some of them are simply more explicitly articulated than others. A description of the Spark Building at Southampton Solent University describes it as a ‘space that promotes interdisciplinary activity and collaboration, enabling staff and students to see and share their learning and teaching experiences, knowledge and research’ (Anon. n.d.: n.pag.). Again, there is a focus on academia as an activity that can be made visible and the idea of opening space to potential collaboration and bringing the outside in as if this were an adequate substitute for making knowledge financially and socially accessible. These spaces are being used by universities to embody (and illustrate) the societal and educational changes that belong in the actual interactions taking place between people.

These buildings articulate both the universities explicit values and its implied ones; none of these projects reimagine their university spaces to make support staff and their work more visible, so a large group of working class and BIPOC members of the university are hidden away by the buildings whilst they may have already effectively been removed from the university by the contracting out of their management. Many of them feature open plan spaces moved through via staircases where ‘planned and improvised encounters between students and faculty’ can take place (Skidmore n.d.: n.pag.). Students, faculty and staff in wheelchairs or with other mobility issues are more or less excluded from these stairwells (and therefore from the ‘improvised encounters’) and are in fact shuttled away from them in elevators.

For eighteen months of the lockdown, the university buildings that contain Parsons School of Design were empty. Whilst the buildings of the university I teach at continue to occupy Lenape Territory in Manhattan, the institution had migrated elsewhere into the kitchens, bedrooms and living rooms of faculty and students. This was a direct merging of the spaces in which we care for our bodies and the now virtual space in which knowledge is passed on. In spite of this, the move online was thought of broadly as an attempt to move an in-person class into an online space as effectively as possible and not an opportunity to rethink everything about the way that the university works and to bring our bodily experiences closer to what we consider to be valuable in an academic space.

The habits and processes of the university

Universities are not only their buildings. In On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life, Sara Ahmed writes that we should consider ‘how we can understand institutions as processes or even as effects of processes’ (2012: 20). The university is not a container in which things happen, but it is the things that happen. This is why it is important to consider the many university processes that are often seen as operating on the periphery of or outside of the university. As Ahmed notes,‘the most ordinary aspects of institutional life are often the least noticeable’ (Ahmed 2012: 20). Most notable amongst these (especially at present) is the job of keeping university spaces clean, the people who do this work and the visibility they have within the institution.

Diversity and now decolonization are two university processes. Ahmed criticizes diversity, pointing out that, ‘[e] ven if diversity can conceal whiteness by providing an organization with colour, it can also expose whiteness by demonstrating the necessity of this act of provision’ (2012: 33). Diversity is often also about visibility. Diverse faces and bodies are those that are considered to differ from a White, cis gendered and able bodied ‘norm’. Diversity in illustrated images depends on the proposition that diversity can and should be made visible, something I will touch on later.

Teaching is another university process. The processes through which we teach illustration can steer us away from a collective understanding of what it is that we are doing as illustrators. Knowledge brought by students (or any of the other non-faculty members of the institution) is undervalued and the expertise of the faculty is privileged. This limits the possibility of transformation of both illustration as a practice and of the people participating in the discipline at the university. If I pass down my techniques for being an ‘illustrator’ to my students then the risk is that they will be replicated but not transformed. Transformation is not measurable.

Being disembodied in the university

Many of the programmes that we teach in are expanding. As student numbers increase it will become more difficult to fit the student body into the space of the university. It seems likely that one of the solutions to this problem will draw on experiences of online teaching during COVID-19. Zoom calls are like seances in which we are called into one another’s virtual presence. Zoom functions as an illustration of a random collection of rooms organized into a grid. This detachment from our academic bodies and from the exposure of academic spaces can be freeing. Every Zoom meeting proposes a special restructuring of the university spaces. Movements and connections between groups of people can be made much more quickly. Some students and faculty may find not having to be physically present in class a release (many of us are engaged in private battles with our bodies) but being in your body at home can also be more or at least differently oppressive than being in your body on campus. When we let students into our domestic spaces (and when we enter theirs) we have to think about what we are modelling for them in terms of a holistic approach to learning that values the well-being and safety of our bodies. It could be dangerous or damaging to impose classroom hierarchies in private spaces.

The start of the pandemic saw students engaged in a time slippage. Adult selves returned to childhood bedrooms. They joined their classes surrounded by the artefacts of childhood. A student in my thesis class, made work depicting them as a giant in their childhood bedroom with limbs emerging from the windows. I noticed that another student in the same class, had written, ‘why do I need a body?’ in her sketchbook. The experience of COVID was of temporal and bodily dislocation. Students were often either in spaces that did not fit their current bodies or they were engaging in wholly disembodied online spaces. These examples seemed to me to be profound illustrations of the moment that we were living through, one that both sublimated and foregrounded our bodies and which brought us virtually into greater intimacy with one another whilst denying us the aspects of learning that rely on being bodies in spaces, ‘[a] s a classroom community, our capacity to generate excitement is deeply affected by our interest in one another, in hearing one another’s voices, in recognizing one another’s presence’ (hooks 1994: 8).

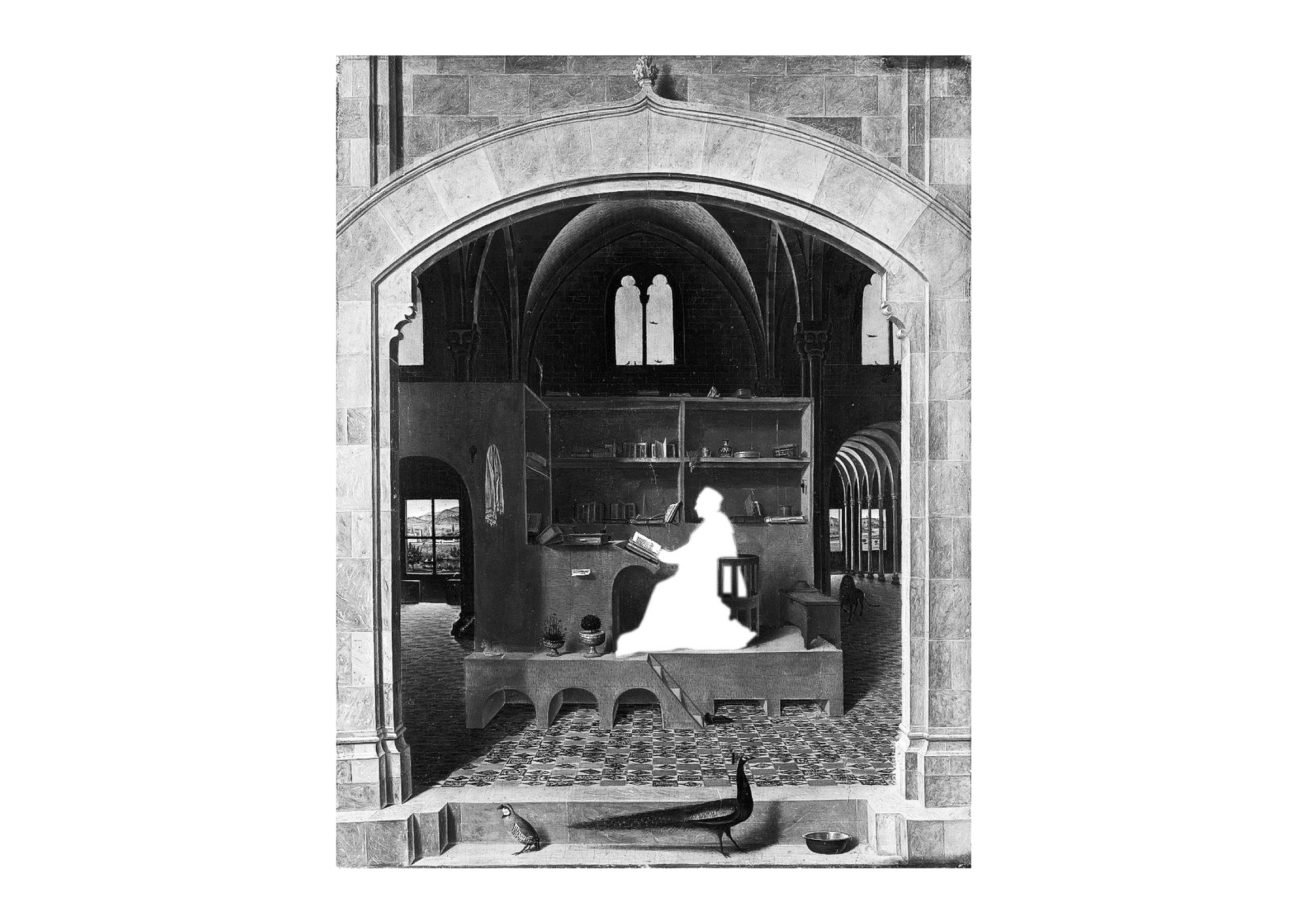

When we become heads in boxes we are given the opportunity to see how physical presence both aids and disrupts learning. On Zoom, where everyone is a head and shoulders, bodies lose some of their impact and their relationship to hierarchy. We are also being continually confronted with sometimes unwelcome images of ourselves. As the pandemic progressed, fewer and fewer students (and faculty and staff) wanted to switch on their cameras. Hito Steyerl writes about the process of being in

front of a camera as a process of erasure (2012: 167). In the case of our laptop camera’s, whether they are on or off, they are documenting our erasure from the spaces of the university. The stress of being on camera may also be greater for those who already feel a sense of not belonging to the spaces of the university,

In those days, those of us from marginal groups were allowed to enter prestigious, predominantly white colleges were made to feel that we were there not to learn but to prove that we were the equal of the whites. We were there to prove this by showing how well we could become clones of our peers. As we constantly confronted biases, an undercurrent of stress

diminished our learning experience.

(hooks 1994: 5)

For students who feel do not belong in the university in the first place, the university reiterates this viewpoint by creating structures and processes that make it harder for them to be present. I have already discussed the way in which the design of new university buildings foreground community and shared learning whilst not fully integrating disabled students into that vision. Students with chronic illness, disabilities or mental health issues might find themselves only semi-present for in-person teaching whilst students from educational backgrounds that prepared them for the university processes are ultra-present demanding more time and attention from their faculty and therefore going onto make the kind of work that will ensure that they maintain their presence. Online learning has the potential to allow those whose bodies (for whatever reason) are made less welcome by the institution to become more present in class.

Successful students are invited back to teach or to give presentations to current students, ‘unsuccessful’ students disappear from the institution. As Jack Halberstam writes that failure, ‘is also unbeing, and that these modes of unbeing and unbecoming propose a different relation to knowledge’ (2011: 23). How can we create more space in the university for knowledge generated by ‘failure’? As hooks points out, learning is often not a happy process but it can be a joyful one. Happiness is something that we are shown an image of, an image that we move towards. Happiness can be visualized. Happy teaching could be thought of as teaching that involves passing a skill to a student in a way that can be measured. This is a reassuring process rooted in the correct way of doing things. ‘The promising nature of happiness is that happiness lies ahead of us, at least if we do the right thing’ (Ahmed 2010: 29). Whilst happiness is a tool of capitalism, joy is bodily and requires trust and conviviality. If we are going to move towards a transgressive community of ideas then faculty and students must feel able to be both vulnerable. This requires joy but does not require happiness.

Illustration as a discipline

A discipline as a conceptual space within a university. Programmes are defined by what they are doing in the context of the other disciplines. Illustration in this context, defines itself in part by what it is not. In his book, What is illustration?, Lawrence Zeegan writes that,

As a discipline, illustration sits somewhere between art and graphic design. Of course, for many practitioners it can feel closer to one end of this spectrum than the other, but in the search for an all-embracing descriptive term, illustration is frequently referred to as a graphic art.

(2009: 6)

This reflects a common conception about where illustration sits as a discipline but does not offer any information that would help us to say why we know an illustration when we see one. It suggests that illustration is dependent on the existence of other creative disciplines in order to exist at all –the discipline of illustration as a negative space within the university for kinds of creative practice that are not Fine Art and not Graphic Design. Looking at descriptions of BA and BFA Illustration programmes, I do not see any real attempts to define illustration and it might not be reasonable to expect to find that here, instead these are descriptions of a set of skills and pathways into industry.

They present Illustration programmes as containers for processes considered necessary for becoming an illustrator. Some commonly listed processes in these descriptions are creativity (it an emphasis on the relationship between visual and analogue ways of making images), storytelling and the development of a personal voice or style.

In being a discipline and maintaining its need for space within the university, illustration must show its seriousness. Because of the relative lack of discourse surrounding the discipline of illustration and because it is a subject that when looked at too closely, either solidifies into industry-based outcomes (editorial, picture book, advertising, etc.) or atomizes into something that can barely be contained. In order to write about illustration, researchers and academics in illustration often borrow seriousness (via research methodologies) from other disciplines. This might be journalism in the case of reportage illustration, or methodology or theory borrowed from the humanities.

hooks writes about the way in which ideas and theories percolate up into academic writing from writers whose work may not be regarded as academic enough to be recognized, ‘hierarchical settings often enable women, particularly white women, with high status and visibility to draw upon the works of feminist scholars who may have less or no status, less or no visibility, without giving recognition to these sources’ (1994: 62). The structure of academic writing facilitates this erasure. Since the murder of George Floyd in 2020 my Instagram feed has become a place where valuable knowledge and information are being shared. TikTok videos cannot be considered academic writing though and it is not easy to trace the knowledge that they contain in a way that meets academic standards. This risks making these thinkers and ideas invisible. Fully illustrated critical and theoretical texts (which TikTok videos and Instagram posts might be considered to be) in which images, design and writing are forming an integrated argument, disrupt the possibility of quotation and referencing. Having your work referred to by other academic texts is one of the measurements of academic success. Although there has been some innovation in the ways in which illustration and design can operate as part of academic texts in recent years, the way in which professionalism is considered in this space seems to mitigate against the development of illustrative thought. Why do we (as illustrators) want to engage in a style of writing that restricts the use of illustration to the point of meaninglessness and that favours certain forms of speech (both visual and verbal)? James Elkins has written critically of the way that illustrations are limited to either use as mnemonics or evidence an argument but style guides for academic journals often restrict or hamper an expanded use of illustration (Elkins n.d.). Systems of citation mean that arguments or quotations cannot be embedded in images and easily quoted. Because of this it might be possible to use illustration as a tool for disrupting the problem that hooks points to; individual claims to ownership of collective ideas. If an illustrator is referencing ideas that cannot be traced to a single original author then they could do it in such a way that stops them from becoming regarded as the originator of these ideas themselves by embedding ideas in images to defeat or at least problematize further referencing. This potential for disruption of established chains of knowledge may be why academic writing has been hostile to illustration.

Defining illustration

[C]ertain ways of seeing the world are established as normal or natural, as obvious and necessary, even though they are often entirely counter intuitive and socially engineered.

(Halberstam 2011: 9)

Histories of illustration often begin with the palaeolithic art found in caves. In History of Illustration, Robert Brinkerhoff and Margot McIlwain Nishimura begin their history with the Cueva de las manos in Patagonia. If this intersection of body, space and communication is truly the seed of the activity we are engaging in today, then only the element of communication remains. This is not a representation of a body, it is (most likely) the direct record of the presence of a body in a space. The caption states that the hands, ‘[f] oreshadow similar assertions of identity found in modern day graffiti’ (2018: 2). Unsurprisingly, graffiti does not make another appearance in History of Illustration. Instead, the caves function broadly as a brief historical waystation on the journey towards the contemporary illustration industry in the United States (and to a certain extent Europe). As students at RISD have pointed out, work from other cultures are also discussed in a way that implies that they exist to supplement our understanding of the US-based illustration canon and art made by people Indigenous to the United States is absent entirely.

When I was researching my Ph.D. in 2014, I was asked to come up with a working definition of illustration by which I could structure my research. The one I arrived at was of illustration as ‘imagesmmparticipating in a communicating text’. Whilst I thought this was as good a definition as any, I was worried (and excited) by the fact that it opened illustration up into an unimaginatively vast and unknowable activity. I no longer regard this as a problem. The problem comes when we try to fit this thing into the discipline space of an institution a process that often leads us to fall back on industry as a stand in for a disciplinary definition.

If the discipline of ‘illustration’ is created by the university, what are its habits within the institution? How might we think about this discipline holistically? In 2019, along with my research assistant Hannah Nishat Botero, I began to look at books about illustration, in order to consider the stories we are telling (and illustrating) for students about what illustration is. The vast majority of the books on illustration are written by White men, something that has only begun to change very recently (with the publication of History of Illustration [2018] and Illustration Research Methods [2020] ). For example, in Heller and Chwast’s Illustration: A Visual History (2008), 338 illustrators are mentioned and of these 22 are women. The majority of these men are White men although it is harder and more problematic to put a number on this. Whiteness is often presumed and I have not yet done the research necessary to discover how the illustrators in this publication identify. My current estimate would be that fewer than fifteen of the illustrators are POC and none are Black or Indigenous. I am not writing this in an effort to create a gotcha moment and I am aware that this kind of analysis is limited. I have included it here to demonstrate how certain bodies are excluded from the image of illustration; White, able bodied people also dominate the illustrators discussed and the bodies represented within these publications. A norm of illustration becomes that people with expertise are White men, this norm is hidden and then absorbed by the discipline. I am not convinced that Illustration as a subject can be separated from this problem, by which I mean that I do not think this is a problem that can be rectified by (e.g.) finding more Black illustrators and images of Black people to include in our illustration histories because this would presume that our foundational ideas about what illustration is are not embedded in colonialism and therefore racialized.

These books on illustration describe illustration a discipline (and a profession) that is a system favouring Whiteness, abled bodied people and hetero-normativity. When education is the passing on of knowledge and expertise and not a process of transformation then White supremacy, heteronormativity and ableism get passed through the discipline along with various skills and ideas of professionalism. The result of this is that books about illustration are often telling a story about the bodies that are allowed to occupy the space of illustration both ‘professionally’ and as subjects.

In some ways, the attempt to be inclusive of other image making histories opens History of Illustration up to these criticisms. Histories are important especially in helping to understand processes and habits of institutions and disciplines. When we give overviews of illustration as a subject we talk about what we think of as important. Because the goal of a history of illustration is to establish a teachable subject within an institutional context, these histories reveal the same issues that academic institutions have; the maintenance of norms and values associated with capitalism and a colonialism. We cannot give a holistic overview of illustration any more than we can give one of speech in general and so when we try, what we end up with is a story of the images we consider most important.

Illustration as failure

Illustration is a clearly defined act of making art, the goal of which is to illuminate a painted (or for that matter any) page – or as say most dictionaries, a visual representation (a picture or diagram) that is used to make a subject more pleasing or easier to understand.

(Heller and Chwast 2008: 11)

Within the discipline of illustration, a failed illustration is one that simply fails to meet the criteria of illustration as it is currently defined. This would be an illustration that was uncommunicative (or that failed to communicate in a way that could be understood), that did not tell a story (or anything at all) that was the result of a failure of creativity (through copying or plagiarism) or that appeared too late to be meaningful made by an illustrator who was unable to establish a voice or who was making use of someone else’s ‘visual language’. This anti-definition begins to suggest some exciting possibilities and also touches some already existing artistic practices in religious or ‘folk’ art.

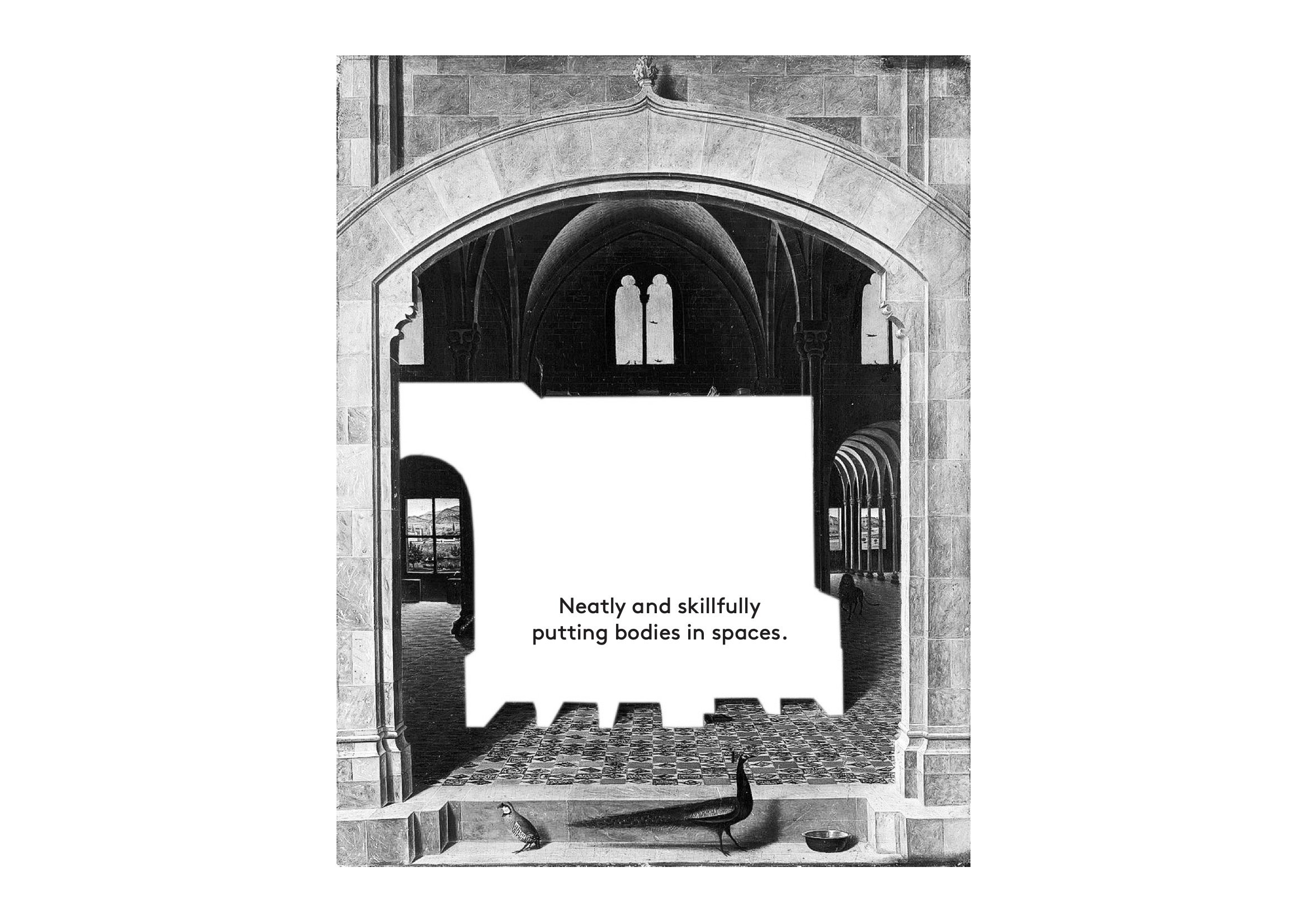

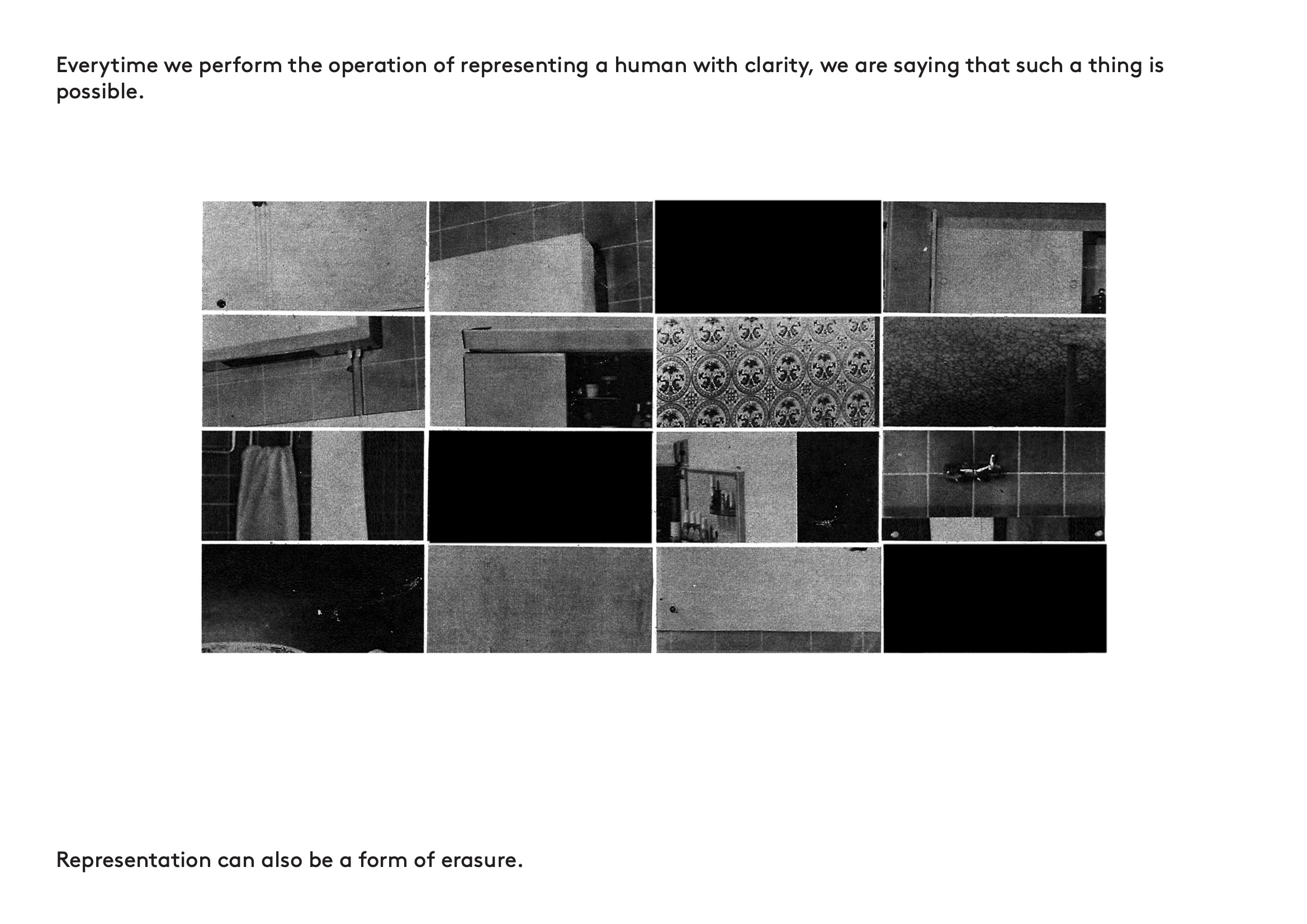

If those are some definitions of failed illustration we need also to consider how illustration fails. Where there is successful generalized communication, there is a dominant group who can believe that the things that they communicate and understand are representative of the population. In most of the contexts that illustration finds itself, communication must be somewhat generalized because the readership of the image is far beyond that which can be sensibly imagined by the illustrator. Our illustrated/illustration stories exclude many kinds of body fro the illustration discipline. Every time we perform the action of representing a human with clarity, we are saying that such a thing is possible. This action risks cementing ideas about how our lives can be represented visually. As Judith Butler asks, what purposes are these claritie serving? (2007: xx). In order for representation (or communication) to be clear, nuance, uncertainty and ambiguity are lost. Representation can be a form of erasure. There are many forms of embodiment that cannot be visualized without making that the subject of the image. If we draw a masculine appearing figure then the only reliable way that we can prevent this figure being read as a cis man is by visually or verbally signalling that they are not. Certain disabilities are invisible. Many members of minority groups present as White in spaces where there is an assumption of Whiteness as a norm. These examples are facets of ‘diversity’ that cannot be visualized and by doing what is necessary to make these things explicit we make otherness the subject of our illustrations. Both sides of this coin result in erasure. Hito Steyerl writes that,

‘[w] hile every possible minority was acknowledged as a potential consumer and visually repre-sented (to a certain extent), people’s participation in political and economic realms became more uneven’ (2012: 170).

Representation does not necessarily have real world consequences (especially in the ways that we hope). A representation can perform an acceptance that has not occurred in reality or provide the comforting appearance that acceptance can happen without the systematic change necessary to make this a reality. Representation can also sometimes be unwelcome, as Hil Malatino writes in Trans Care, ‘many trans folks resist, both implicitly and explicitly, what photographic theorist John Tagg calls “the burden of representation” (1993) and the institutional demands for transparency, legibility, and the determinacy and continuity of identity that come with it’ (2020: 27).

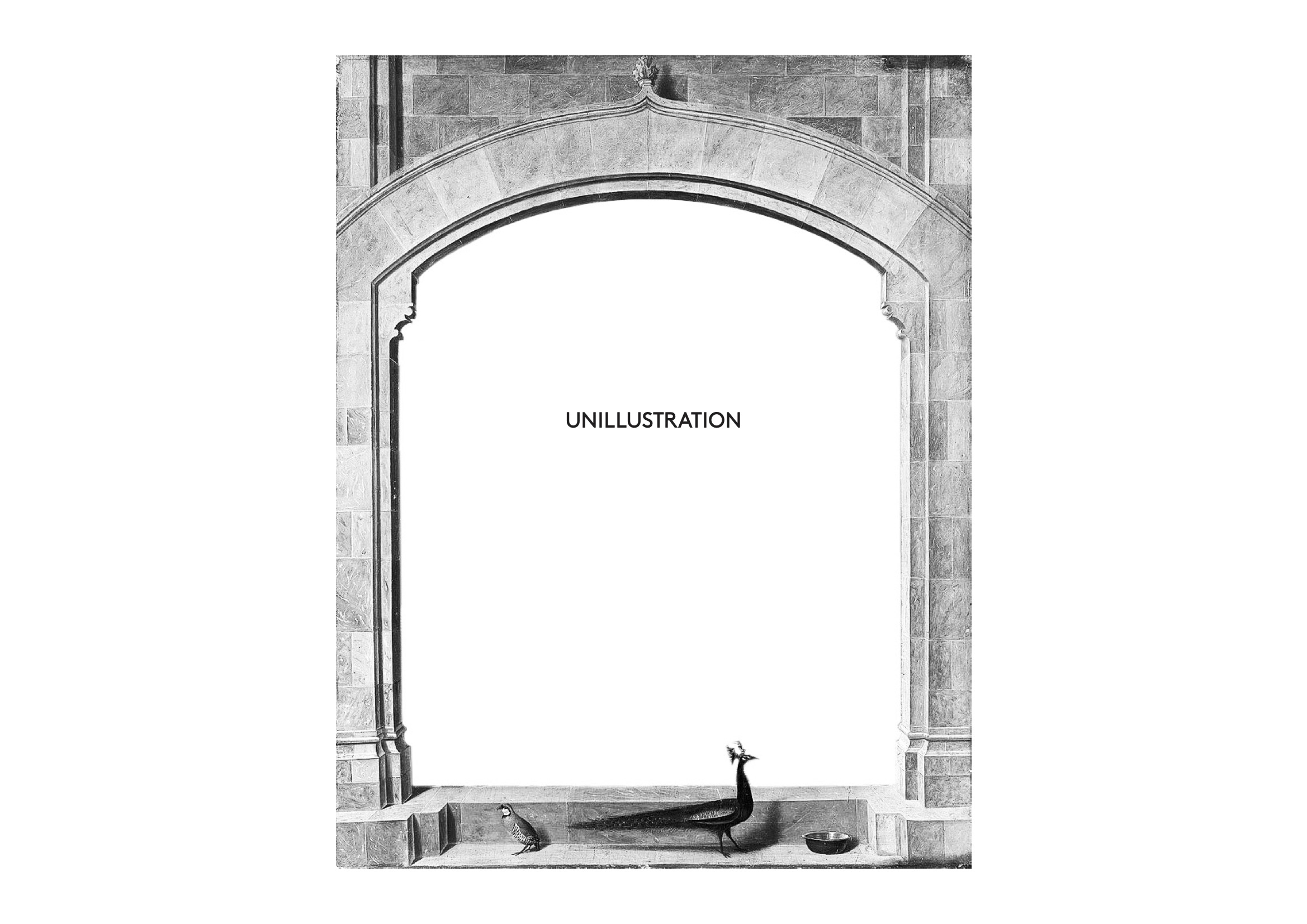

Unillustration

I sometimes think that illustrators are all haunted by the idea that what we are doing is essen-tially frivolous and shallow and so we spend our time trying to prove that instead illustration is serious and vital. In The Mushroom at the End of the World, Tsing talks about how the meaning of things changes when they are scaled up or scaled down. Many things that are powerful on a small scale have their meaning and their power diluted when they are scaled up. For example, if illustration were scaled down to the point where every street was served by an illustrator, we can envisage what that person is doing without resorting to idea of professionalism or seriousness. When illustration is at its most immediate and trivial, it is most clear that it is vital.

‘Undoing Empire also means undoing oneself. This is never a purely negative undoing, because it also means becoming capable of something new’ (Montgomery and bergman 2017: 25). In his book, Postmodernist Fiction, Brian McHale describes a kind of illustration that is ‘destroying itself’ (2003: 189) by failing to communicate the narrative that it is participating in and instead (by means of this disruption) drawing attention to the book as a construct. These ard illustr-ations that are, ‘pure demonstrations of the visuality and therefore the three-dimensionality and materiality, of the book’ (2003: 190). What is being destroyed here is not the element of comm-unication but the idea of an illustration as an aid to clear communication and a window through which the imagination can travel. Even seemingly meaningless or failed communication can still communicate something and an illustration that sabotages the text that it participates in (McHale gives the example of Max Ernst’s 1934 novel Une semaine de bonté) is communicating about illustration itself.

I would like to suggest two possible ways forwards for illustration to exist as a discipline: The first is unillustration, the shadow of illustration is an already existing space that McHale’ ‘Anti-illustration’ touches. Unillustration is not a discipline it is an activity entirely dedicated to ques-tioning unpicking, obscuring and shadowing. A discipline at odds with everything around it (and itself). This discipline might occupy the negative space within the university for kind of creative practice that are not Fine Art and not Graphic Design, it would be an examination of what illustration is not and should not be. A continuous and generative turn inwards and dismantling.

The second would be illustration. Untethered from the need to define itself against other disciplines, illustration would be free to roam. In ‘The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction’, Walter Benjamin wrote that, ‘[l] ithography enabled graphic art to illustrate everyday life’ ([1936] 2008: 2). Although Benjamin is not quite talking about this, it is a tantalizing offer of a kind of illustration fully enmeshed and integrated in our daily lives. This means that in the spaces where we find illustration it may not be operating in ways that are moral or good. It may not always be communicating in ways that are legible.

Illustration as a mechanism for communication is a parasite on all of the other spaces in the university. Not just transdisciplinary but trans spatial. Present and equally valuable in thesis papers as in corridors, cleaner’s cupboards and on toilet walls. ‘And what does the under-commons of the university want to be? It wants to constitute an unprofessional force of fugitive knowers, with a set of intellectual practices not bound by examination systems and test scores’ (Halberstam 2011: 8).

References

Ahmed, Sara (2010), The Promise of Happiness, Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press.

Ahmed, Sara (2012), On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life, Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press.

Anon. (n.d.), ‘Iconic higher education design: The Spark Building, Southampton Solent University’,

https://universitybusiness.co.uk/estates/design-showcase/. Accessed 20 October 2021.

Benjamin, Walter ([1936] 2009), ‘The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction’, in One Way Street and Other Writings (trans. J. A. Unwin), London: Penguin.

Biss, Eula (2014), On Immunity, London: Fitzcarraldo Editions.

Butler, Judith (2007), Gender Trouble, London: Routledge.

Barbosa, Livia (2012), ‘Domestic workers and pollution in Brazil’, in B. Campkin and R. Cox (eds),

Dirt: New Geographies of Cleanliness and Contamination, London and New York: I. B. Taurus, pp. 25–33.

Campkin, Ben and Cox, Rosie (eds) (2012), Dirt: New Cartographies of Cleanliness and Contamination, London and New York: I. B. Taurus.

Doyle, Susan, Grove, Jaleen and Sherman, Whitney (eds) (2018), History of Illustration, New York: Fairchild Books.

Elkins, James (n.d.), ‘An attempt at theory’, Writing with Images, http://writingwithimages.com/18-

an-attempt-at-theory/. Accessed 7 May 2022.

Grafton Architects (n.d.), ‘Townhouse, Kingston University London’, https://www.graftonarchitects.ie/Town-House-Kingston-University-London.

Accessed 9 January 2023.

Halberstam, Jack (2011), The Queer Art of Failure, Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press.

Heller, Steven and Chwast, Seymour (2008), Illustration a Visual History, New York: Abrams.

hooks, bell (1994), Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, London and New York: Routledge.

Jagoe, Rebecca and Kivland, Sharon (2020), On Care, London: Ma Bibliothèque.

la paperson (2017), A Third University Is Possible, Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis University Press.

Malatino, Hil (2020), Trans Care, Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis University Press.

McHale, Brian (2003), Postmodernist Fiction, London: Taylor & Francis.

Montgomery, Nick and bergman, carla (2017), Joyful Militancy, Chico, CA and Edinburgh: AK

Press.

Moton, Fred and Harney, Stefano (2004), ‘The university and the undercommons’, Social Text 79,

22:2.

Skidmore, Owings (n.d.), ‘Building on a progressive legacy’, Merrill, https://www.som.com/projects/university-center-the-new-school/. Accessed 20 October 2021.

Steyerl, Hito (2012), ‘The spam of the earth: Withdrawal from representation’, in The Wretched of the Screen, Berlin: Sternberg Press, pp. 160–75.

Tuck, Eve and Yang, K. Wayne (2012), ‘Decolonization is not a metaphor’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1:1, pp. 1–40.

Wainright, Oliver (2021), ‘“It sounded crazy”: Palatial six-storey hymn to social interaction is Britain’s

best new building’, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/oct/14/

britains-best-new-building-riba-stirling-prize-kingston-university-town-house. Accessed 4 July

2022.

Zeegan, Lawrence (2009), What Is Illustration?, London: Rotovision.