1. The Nomadic Illustration

(2015)

Towards the end the research undertaken for my PhD, I came across images that were appearing repeatedly in different contexts online. In some instances the captions or articles that accompanied these images were communicating broadly similar messages, in other cases an image was being given a wholly new narrative when it changed context. I became interested in the idea that these images might be nomadic or wandering images, moving from webpage to webpage, and I wondered how they were functioning as illustrations.

In this paper I am defining an illustration as any image that participates in a complex text presented as a communicating artefact (for example, a communicating artefact could be a website, a text message, a book or a t-shirt). The definition of text I am using is an extension of Mieke Bal’s ‘narrative text’ or the communicating layer of narrative composed of signs (Bal, 2009:5). A text may be composed of words, word and pictures or pictures only and every element of the text should be considered in it analysis. The way that the text communicates is also altered by the artefact in or on which it appears, for example a narrative delivered as a sequence of tweets may be presented using exactly the same words in a book but the two will inevitably communicate differently. In using this definition I hope to emphasise the limitation of attempting to consider separately words and images in a text where they are presented together. Although I acknowledge that the definition of illustration given here is not perfect, it allows me to discuss images which would normally fall outside of the illustration discussion i.e. images not created by an artist or illustrator in response to a brief.

Illustrative images are ‘wandering’ online continuously, a particular news photograph may become representative of an event and subsequently circulate across news websites and social media. As Kenneth Goldsmith has shown (2013:72-77), the context an image appears in online also changes depending on the device (or format) you are using to look at it with. Although these areas of discussion are adjacent to the argument made by this paper they will not be covered here (they are however discussions that should interest illustrators). The images that will be discussed here are ones which have associations with narratives that are to a greater or lesser extent fictional and which set up particularly interesting relationships between the texts that they are used to illustrate. Due to the nature of the images I am discussing some of the references used by this paper are necessarily unreliable. Where this is the case I have gone as far as possible to check that the information given is corroborated. Before I start to discuss what a nomadic illustrations might be or do I’m going to introduce the ideas that form the background to this paper. The first of these is the idea of net neutrality discussed by Kenneth Goldsmith in his 2013 book Uncreative Writing.

Net neutrality advocates claim that all data on the network be treated as equal, whether it be a piece of spam or a Nobel Laureate’s speech. (Goldsmith, 2011:34).

Goldsmith is interested in treating language as material and I am interested in the way that this idea can be applied to illustration. Firstly, it is important to look online at low quality images functioning as illustrations whose authorship is either unclear or impossible to define and to consider them as of equal interest or importance to the images created by illustrators. I am also interested in the implications of Goldsmith’s ideas about the materiality of texts - that existing texts provide the material for creating new ones – for illustration. In illustration we often limit our consideration to images that have been made by a particular illustrator (usually in answer to a brief) but it is clear that illustration may also occur when it is not possible to locate its

author and an image may be wholly appropriated and still successfully illustrate. Online, images such as this are already functioning as illustrations in much the same way that photography has been functioning illustratively within print media for many years.

In ‘The Photographic Message’ Roland Barthes discusses how ‘determinate meaning’ is created by the context in which we first encounter an image, in Barthes’ case this is a page of a newspaper.

The press photograph is a message. Considered overall this message is formed by a source of emission, a channel of transmission and a point of reception. (Barthes,1977:15).

As WJT Mitchell anticipates in his book The Reconfigured Eye (1991) this is interesting if we consider how quickly images are now moving from context to context online and when even one context, a webpage of a particular newspaper for example, might change over the course of a day, from person to person (depending on their browser history), or even whilst you are looking at it (85). Later in ‘The Photographic Message’ Barthes describes photographs in the following way,

…whatever the origin and destination of the message, the photograph is not simply a product or a channel but also an object endowed with structural autonomy. (Barthes,1977:15).

Barthes means (I think) that a photograph has a meaning that cannot be determined by the words that accompany it, a caption may mask a photograph by appearing to give it meaning but the photograph will always to some degree remain outside of meaning (2000:34). Reading this though, I was caught by the idea of images with ‘structural autonomy’. Autonomy implies independence, what might an autonomous image do? If the autonomy is structural might some images be composed in such a way as to make them autonomous? There is another term that has triggered some of the thinking in this paper. It appears in Umberto Eco’s Open Work and it is the idea of ‘work in movement’, the antithesis to a work which,

…may well vary in the ways it can be received but which always maintains a

coherent identity of its own and which displays the personal imprint that

makes it a specific, vital, and significant act of communication.(1989:20).

The work in movement on the other hand is, ‘characterized by the invitation to make the work together with the author.’ (1989:21). This has obvious implications for the way that texts are created online (collaboratively or contingently) but here I’m using it as a way of thinking about images or artworks that are on the move –literally being transferred from context to context through a process of dragging and dropping. It’s important to note that I’m am using these terms at some distance from the way in which they were meant by Barthes and Eco but that I believe that this bending of their intentions is worthwhile as a way of beginning to locate the ideas I will be discussing in this paper.

The next text which was key to my formulation of the nomadic illustration is Geoff Dyer’s book The Ongoing Moment (2005). In this book Dyer traces a thread through the history of photography using repeating subjects as his organising principle. For example, he describes becoming interested in portraits of people wearing hats and how, ‘the idea of the hat became an organising principle or node’ (2006:6) in his history of photography. There are two key ideas here, firstly that photographers taking photographs of hats are sharing in a particular moment or idea, the idea is a space that they enter into when they photograph a particular hat (for example) in a particular way and secondly that an image might operate as a node around which artistic or photographic practices might gather. One of the examples that Dyer refers to in The Ongoing Moment is the repeating subject of the blind busker and he gives examples of the busker’s appearances in photographs by Walker Evans in 1938, Ben Shahn in 1932 and André Kertész in 1916. Dyer suggests that there is something about the subject of the blind busker that photography seeks out,

The blind subject is the objective corollary of the photographer’s longed for

invisibility. It comes as no surprise therefore – the logic of the medium seems

almost to demand it – that so many photographers have made pictures of the

blind. (Dyer, 2007:13).

If the repetition of the blind busker as a subject in the history of photography is suggested by the subject’s relationship with the nature of the medium then perhaps there are images that suggest repetition within particular contexts due to their content their subject matter or their ‘structure’.

The images that first led me to the idea of the nomadic illustration are ones that I initially encountered on a blog called ‘A Gay Girl in Damascus’ (G.G.I.D). This blog came to public attention in 2011 at the same time that the uprisings in Syria were beginning. It claimed to be the work of a young gay Syrian American woman living with her father in Damascus and it discussed Amina’s life, her experiences as a gay Muslim woman and her involvement with the protests in Damascus (Marsh, 2011:24). Amina’s blog posts included extracts from her novel, her poetry and photographs, maps and video clips lifted from other online sources, mostly news media sites such as the BBC, Guardian and Reuters and Wikipedia 1.

Amina Arraf never existed, she was the creation of an American PhD student living in Edinburgh 2 (Addley, 2011) and I became interested both in the construction of the character of Amina through the G.G.I.D blog and in the images that were used in this construction. The first images I encountered in the G.G.I.D deception that had ‘moved’ were photographs that Tom MacMaster used as Amina’s profile picture both on her Facebook page and her Blogspot profile. These were in fact images that had initially appeared on the Facebook page of a Croatian woman living in London called Jelena Lečić (Randhawa, 2011:9). The photographs of Lečić made one move from illustrating her own Facebook identity to illustrating the facebook identity of the non- existent Amina. They then moved repeatedly online as activists took up ‘Amina’s’ cause, one image of Lečić was used as a reference for a drawn portrait of Amina that appeared on a ‘Free Amina’ poster and has subsequently been used as part of a facebook campaign to free another (real) Amina 3 .

The Lečić portrait was one of the elements of the Amina Arraf costruction that began to raise alarm bells with readers. Lečić contacted the Guardian to say that images they were describing as showing the author of the G.G.I.D blog were in fact of her (Randhawa, 2011:9).

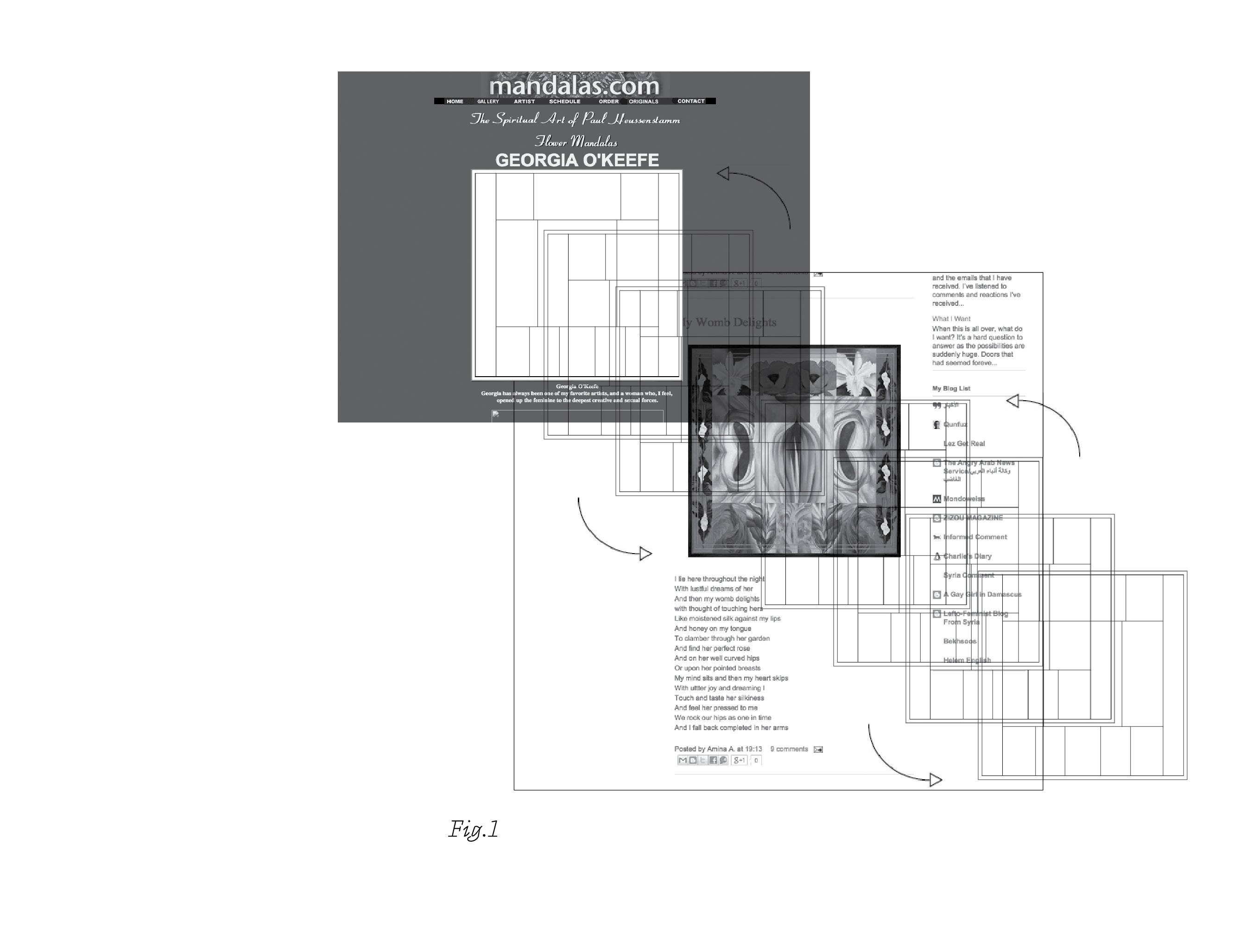

In the aftermath of the deception, very few people looked seriously at the many other images that appeared on the blog, I considered them as illustrations (images participating in a complex text) and in this respect some were more interesting than others. The image I want to discuss here appears as part of Amina’s blog post for the 21 st May 2012, where it accompanies a poem entitled ‘My womb delights’. The image is a montage of paintings by Georgia O’Keeffe which emphasises the erotic aspects of her imagery. The montage was created by Paul Heussenstamm, an artist who produces images of mandala’s and sells them from his website as greetings cards and prints. The image appears on his website with the following line of text, ‘Georgia has always been one of my favourite artists, and a woman who, I feel, opened up the feminine to the deepest creative and sexual forces.’ 4 Whilst attempting to track down where MacMaster had taken the image from originally, I encountered it on a number of other blogs (Figure 1) including;

• A View from my Laundry Room, Tuesday May • Art 160, Women in Art, Friday April 30 th , 2010 6

• Clarafications, Dec 14 th , 2009 7

On each of these blogs the image is wrongly attributed to O’Keeffe and is being used to substantiate a particular reading of her work, one concerned with female sexuality and the erotic, a reading which O’Keeffe herself disputed. For example, on ‘A View From My Laundry Room’ the image is shown along with the caption, ‘No post about Georgia O’Keeffe would be complete without a little erotica!’ 8 and on Clarafication the blog post that includes the image is entitled ‘Georgia O’Keeffe Painted Vaginas’. It is interesting that an image not by O’Keeffe has - in one corner of the Internet and for a relatively short span of time - become an illustration of a certain idea about her career. The mandala image made by Heussenstamm is a composite, a particularly reductive edit of O’Keeffe and her work. There is a link here to The Ongoing Moment. Dyer discusses how George Stiglitz (O’Keeffe’s husband) obsessively photographed parts of O’Keeffe’s body. He was particularly interested in her hand and her breasts, Dyer calls this an ‘ongoing compositional portrait’ of O’Keeffe that Stiglitz was building over time (2007:77). In the case of the Heussenstamm mandala, O’Keeffe’s own work has been replaced by a compositional portrait of it.

The Heussenstamm O’Keeffe composite, was for a short time nomadic. It moved from context to context on line, was downloaded and re-uploaded, it wandered from one blog, was dragged and dropped onto a desktop and uploaded to another blog. The contexts which gave it meaning were repeatedly altered. When we think about images that do this, the first word that springs to mind is ‘meme’. The term meme is taken from ‘Memes: The New Replicators’, chapter 11 of Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene (1976). Dawkins definition of a meme is of an idea the replicates itself and is passed through society. Particular artworks such as symphonies may be composed of many memes and the images discussed in this paper may both behave as memes on their own whilst also being composed of several memes themselves. The term is now also defined by the OED as referring to an image ‘that is copied and spread rapidly by Internet users, often with slight variations.’ The images I am discussing here are not memes, they are often not humourous and the variations they display are very slight and have more to do with the degradation of digital information as it circulates online than alterations made by users. It is worth considering them in the context of memes though as it is possible that they do share with successful memes properties which make them more likely to circulate online.

Discussing memes (in the sense of the word’s contemporary usage) for The Smithsonian magazine, James Glieck gives the example of a portrait of George Washington suggesting that the appearance of the portrait has become a substitute for the actual appearance of Washington, ‘“This may not be what George Washington looked like then,” a tour guide was overheard saying of the Gilbert Stuart portrait at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “but this is what he looks like now.”’ 9 So an image such as the O’Keeffe mandala becomes a proxy for a certain idea about her work. Similarly, Gombrich comments on the ‘Nuremberg Chronicle’ with woodcuts by Dürer’s teacher Wolgemut,

…as we turn the pages of this big folio, we find the same woodcut of a

medieval city returning with different captions as Damascus, Ferrara, Milan

and Mantua. Unless we are prepared to believe these cities were as

indistinguishable from one another as their suburbs may be today, we must

conclude that neither the publisher nor the public minded whether the

captions told the truth. All they were expected to do was to bring home to the reader that these names stood for cities. (2002:60)

This is another example of the way in which an image may be used as a shorthand for an idea rather than as evidence of something that actually exists. Later in his article, Gleick describes a meme as potentially having an existence ‘independent of any physical reality’ which returns us to the idea of the independent or autonomous image.

On February 25 th 2010 a shark filled aquarium in a Dubai shopping centre cracked open (BBC). On June 1 st 2012, a ‘Your News’ user named Jenny Porter uploaded a photograph of a flooded Toronto Royal Bank Plaza shopping centre to the CBC news website (Your news: Editor’s Picks). In June 2012 a shark tank did not collapse in the Kuwait Scientific Centre and on December 19 th 2012 another shark tank in the Shanghai Orient shopping centre did collapse killing the sharks inside it (Huffington Post).

The sharks in a shopping mall image was created by Jamie King using Jenny Porter’s picture of the Toronto Royal Bank Plaza shopping centre (Figure 2). King posted it on Twitter and Imgur on June 1 st with the caption, ‘Things at Union Station are worse than we thought’ 10 Since then the image has appeared on a YouTube news channel called RodsburghNewsLive (uploaded on August 21 st 2013) which locates the incident in the Philipines but also shows a real image of sharks in the Shanghai mall 11; on Tumblr with the suggestion that it shows the aquarium in Dubai; the photograph circulated during Hurricaine Sandy with a claim that it showed sharks swimming in a flooded New Jersey subway station (Snopes, 2012); and other appearances on social media have seen the image attributed to the shark tank collapse that did not happen in the Scientific Centre in Kuwait (HoaxSlayer, 2012). There are a host of associate images showing sharks swimming through flooded streets, these images are all also montage and are also regularly recycled online (Hughes, 2011 and Snopes 2012).

The ‘Sharks in a Mall’ image is fictional but often appears in association with real events in which shopping centre aquariums really have cracked or burst. Whilst the image stays the same, the location of the flooded shopping mall it is supposed to depict moves. The image is located by the caption that accompanies it. In the original image of the Toronto shopping centre (and in some of the images I have included in this paper) two men can be seen standing in the top left hand corner of the image, if the water was deep enough to hold the sharks it could not also be deep enough for the men to be standing on the floor, therefore as soon as the reader notices the men she realises that the sharks must have been added digitally or at the very least that there is something odd about the image. Barthes writes that ‘the text directs the reader through the signifieds of the image, causing him avoid some and receive others’ (1982:40). Captions direct our reading of the image even when there is an aporia within the image itself. The sharks in a shopping mall image is a composite and therefore does not depict any real event, it has however become associated with a cluster of real events involving aquariums in shopping centres. In this way the image has become an organising principle (or class) within which these (real) news stories are gathered.

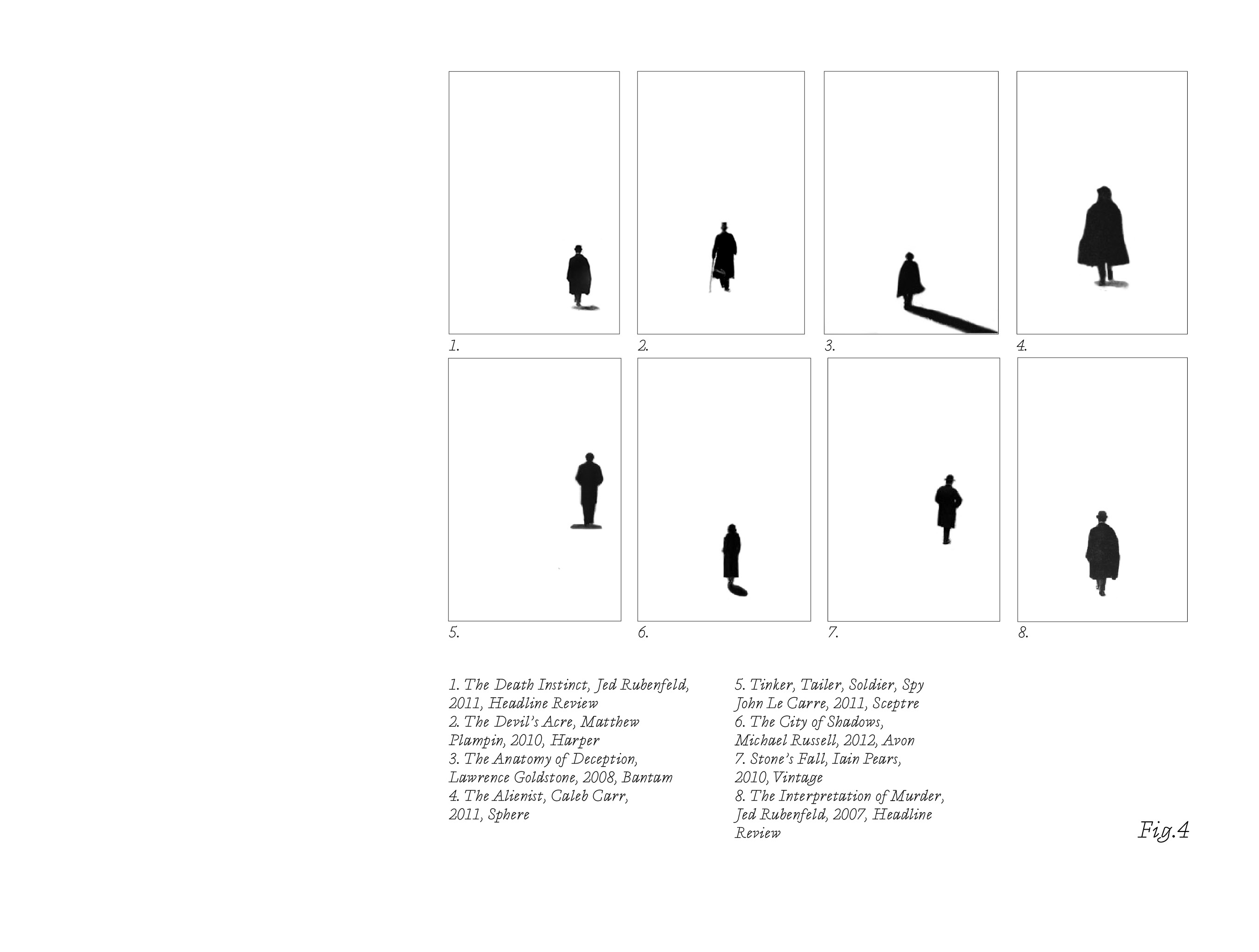

Are nomadic images confined to the Internet? An example of an image which can become a classifying principle for a particular narrative both on and offline is the book cover. In UK publishing certain conventions have developed around particular genres of fiction, one example of which is the black and white image of a ‘tiny man running/walking into the distance’ (Horspool, 2012) which can be found on the covers of spy thrillers (Figure 3). For example, the 2011 edition of John Le Carre’s classic cold war spy novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy has such a cover, The Interpretation of Murder by Jed Rubenfeld (2007) has a similar cover as does Child 44 by Tom Rob Smith (2009). This cover becomes both an indicator of the contents of the narrative and a node around which certain types of narrative gather. Geoff Dyer might argue that the man in the image is the same man every time – he is someone that graphic designers search for when they are tasked with providing a cover for a particular kind of book. Many areas of publishing are being covertly organised into classes by the images displayed on their covers. This is something that is pointed to as evidence of the poverty of book cover design in the UK (Horspool, 2012) but it is interesting when you consider the potential for illustrations to act as doorways between the narratives that they illustrate linking them in the way that hypertext links sections of

writing.

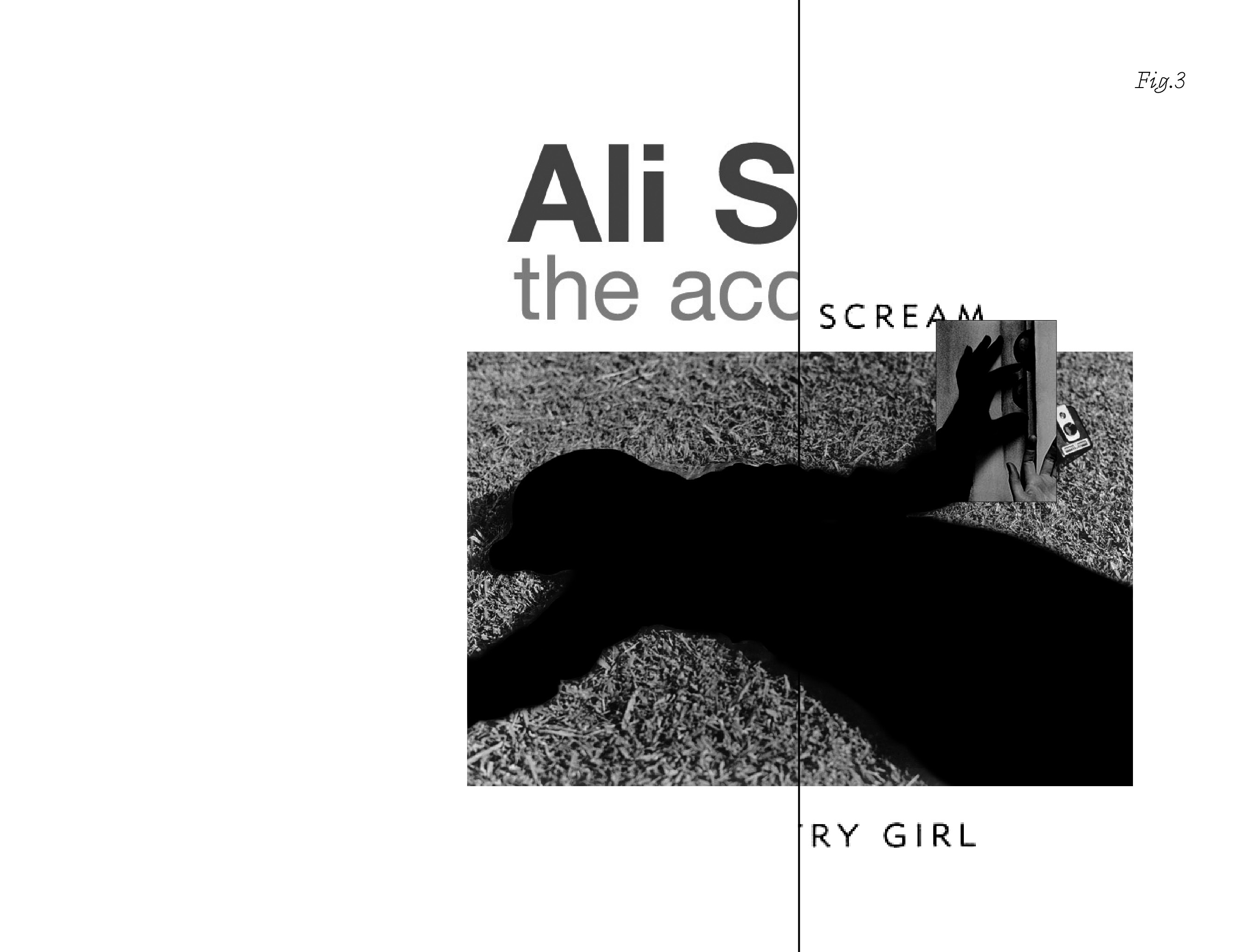

Having given you several examples of what it is that I mean when I refer to nomadic illustrations, I began to wonder if the quality that makes an image move is a lack of clear authorship. Perhaps authored images, by which I mean images that retain a strong link with an identity of the person who made them are less free to move than ones whose authorship is not so obvious. So with this in mind, I looked for examples of moving images which retained a clear link to their author. William Eggleston’s photography is often used to illustrate book covers 12 and his photograph Untitled (1975) appears on the cover of both Ali Smith’s novel The Accidental (2008) and Primal Scream’s single Country Girl (2006) (Figure 4). Untitled (1975) is a photograph of Eggleston’s red haired muse Marcia. On the cover of The Accidental Marcia might appear to be Amber, a charismatic character described as having red hair or Astrid who photographs other characters in the novel with a digital camera (O’Hagan, 2006). On the cover of the Primal Scream album cover Marcia is, it is implied, the girl being described by the song. William Eggleston described the photograph as showing Marcia ‘whacked out on Qaaludes’(O’Hagan, 2006). In the case of this image, the identity of the girl in the photograph becomes nomadic as well as the image itself.

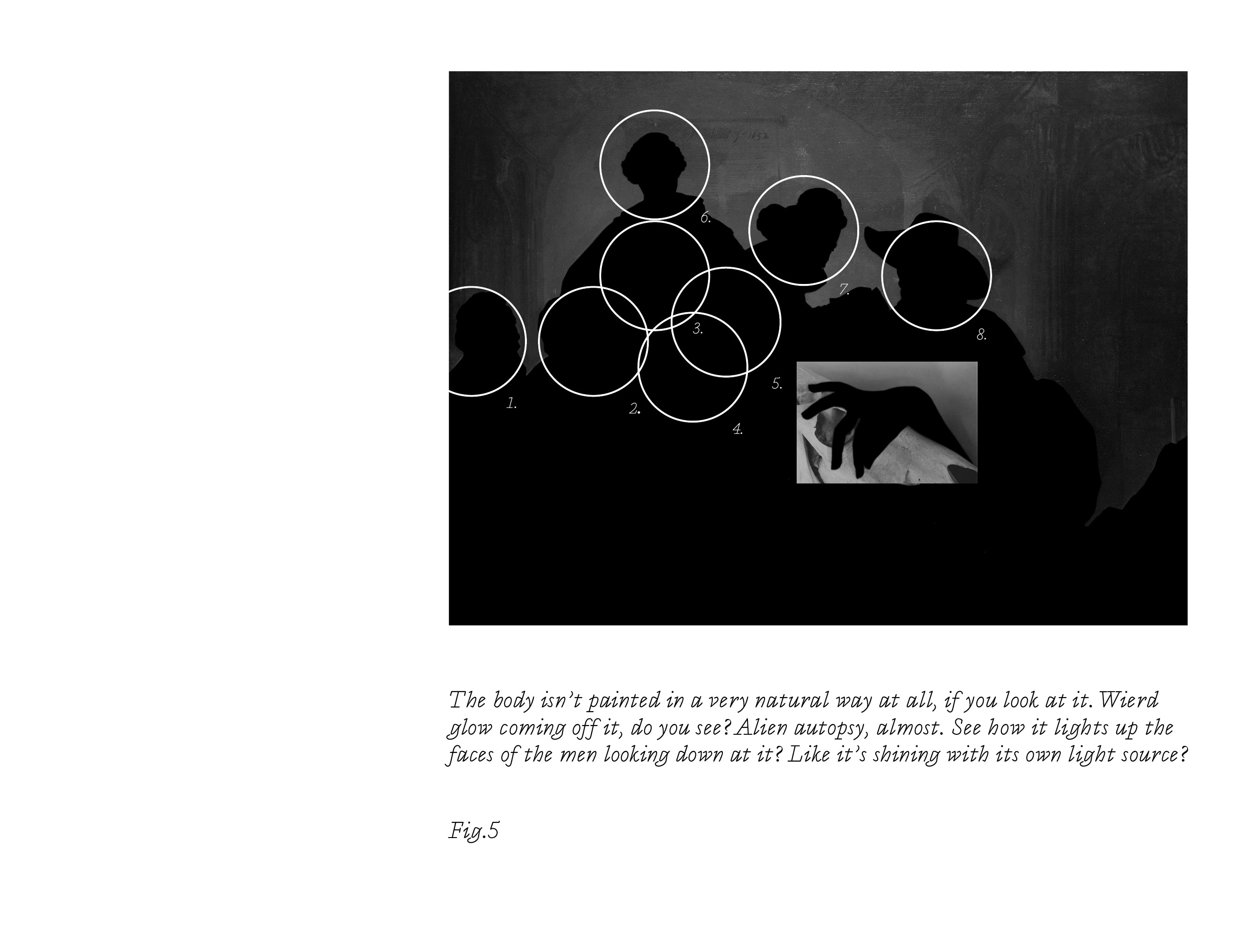

Having given you several examples of what it is that I mean when I refer to nomadic illustrations, I began to wonder if the quality that makes an image move is a lack of clear authorship. Perhaps authored images, by which I mean images that retain a strong link with an identity of the person who made them are less free to move than ones whose authorship is not so obvious. So with this in mind, I looked for examples of moving images which retained a clear link to their author. William Eggleston’s photography is often used to illustrate book covers 12 and his photograph Untitled (1975) appears on the cover of both Ali Smith’s novel The Accidental (2008) and Primal Scream’s single Country Girl (2006) (Figure 4). Untitled (1975) is a photograph of Eggleston’s red haired muse Marcia. On the cover of The Accidental Marcia might appear to be Amber, a charismatic character described as having red hair or Astrid who photographs other characters in the novel with a digital camera (O’Hagan, 2006). On the cover of the Primal Scream album cover Marcia is, it is implied, the girl being described by the song. William Eggleston described the photograph as showing Marcia ‘whacked out on Qaaludes’(O’Hagan, 2006). In the case of this image, the identity of the girl in the photograph becomes nomadic as well as the image itself.Another example of an image with strong associations with its author and which also displays nomadic tendencies is The Anatomy Lesson of Doctor Nicholaes Tulp by Rembrandt (1632). Before I start to discuss this image’s movement through fictional narratives, I should also say that images such as this that are part of the art historica canon also move between art history texts and the history of art writing might be said to be one of moving or contagious illustrations. Many of the images of artworks that appear in art history texts are illustrations acting either as mnemonics or supporting a particular argument (Elkins, 2014). It is interesting to consider (as Elkins does) that illustrations might also be used to support or undermine an academic argument. The Anatomy Lesson appears in Rings of Saturn by W.G.Sebald. The image appears twice, first as a double page spread then as a close up (2002: 14-16) and accompanies a section of the novel which describes it. Sebald’s narrator claims that the hand of the dissected body is on the wrong way around as the tendons that can be seen in the painting would in fact not be visible from the angle that we are looking at them and suggests that this is deliberate commenting that ‘the much admired verisimilitude’ of Rembrandt’s painting ‘proves on closer examination to be more apparent than real’ (2002: 16). Elkins is somewhat critical of Sebald (conflating Sebald with his narrator) for what he argues is a mistaken analysis of the painting (2014). It seems possible though that a more conventional argument makes sense here; Sebald is using this part of Rings of Saturn to make a warning about verisimilitude. We may not be able to trust Rembrandt’s painting (or the discussion of it) and we may not be able to trus that the voice of the narrator is synonymous with the voice of Sebald.

The painting also appears in the game Deux ex: Human Revolution (2011) and is referenced in a promo video for the game (Rawlings, 2011). On his blog for the Welcome Trust Tomas Rawlings argues that the use of the painting is linked to the games themes of scientific and technological advancement from the birth of modern anatomy to the future in physical and technological augmentation being explored by the game. Here, the painting is being used as a historical reference point linking a fictional future to a past that can be located to the painting as an artefact. My final example is a reference to the painting in Donna Tartt’s 2013 novel The Goldfinch;

Now, Rembrandt,” my mother said, “Everyone always says this painting is

about reason and enlightenment, the dawn of scientific inquiry, all that, but to me it’s creepy how polite and formal they are, milling around the slab like a buffet at a cocktail party. Although - “ she pointed - “see those two puzzled

guys in the back there? They’re not looking at the body - they’re looking at us. You and me. Like they see us standing here in front of them - two people from the future. Startled. ‘What are you doing here?’’ (27: 2013)

The text that precedes this extract describes the image in some detail. Tartt’s writing conjures the painting through a process of ekphrasis (Figure 5). Ekphrasis is a Greek term for the description of a work of art so that it might appear in the mind of the reader. Elkin’s points out that ekphrasis can balance an illustration, arguing that in The Rings of Saturn the use of a description of what the narrator sees through a window balances the photograph of the window on the facing page (2013). Ekphrasis might be regarded as a form of illustration in its own right, as it supplies an image which (necessarily in this case) accompanies a piece writing. It differs in this sense from any other narrative description because it is directed towards a single, still image.

Interestingly the character of the mother who is describing The Anatomy Lesson to her son in The Goldfinch repeats the point about the cadaver’s hand being depicted wrongly (2013: 27) suggesting again that when an image wanders some of the ideas that it has been associated with may wander too. In the case of The Anatomy Lesson of Doctor Nicholaes Tulp, the image is often being used to make a link between the narrative of the text it is appearing in and the moment at which the original painting was created. The image is being used for the time period that it refers to, connecting fictional characters to a real event (Rembrandt’s creation of the painting) and a historical moment (the birth of modern anatomy).

Interestingly the character of the mother who is describing The Anatomy Lesson to her son in The Goldfinch repeats the point about the cadaver’s hand being depicted wrongly (2013: 27) suggesting again that when an image wanders some of the ideas that it has been associated with may wander too. In the case of The Anatomy Lesson of Doctor Nicholaes Tulp, the image is often being used to make a link between the narrative of the text it is appearing in and the moment at which the original painting was created. The image is being used for the time period that it refers to, connecting fictional characters to a real event (Rembrandt’s creation of the painting) and a historical moment (the birth of modern anatomy).It is now becoming apparent that nomadic images do not simply move online (although The Anatomy Lesson is a painting that has moved online too 13 ), that this is not necessarily a contemporary phenomenon, and that perhaps an image an be used as a shorthand for the things it connotes. My next example of a moving image is possibly not an image at all; it is the black page that appears in Lawrence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759). In the novel the black page invites the reader to contemplate the death of Yorick, it is a symbol of mortality and a narrative pause, in fact it is a denial of narrative, in that it is an absence of event. In Writing with Images James Elkins includes several examples of the way in which the black page appears in different editions of Tristram Shandy. Some editions of the book don’t include the square at all, in others it takes on different shapes and sizes (Elkins, 2014) –occasionally it appears full bleed. This suggests almost that the blackness is a strata that underpins the narrative and that the frame that surrounds it in any given edition of the text is simply a window into the blackness (Figure 6). In fact, Sterne had probably borrowed the black square from the tradition of mourning pages, a seventeenth century tradition of including a black page in orders of service for funerals or in a memorial booklets (Trettien, 2012). The black page appears as another kind of narrative refusal in Salvador Plascencia’s People of Paper. In the book, the characters begin to recognise the presence of an omniscient narrator (the author) who is referred to as ‘Saturn’ (2007). Here the black squares represent attempts by the characters to limit the access that the author has to their thoughts, they are refusing to be narrated (2007:189).

The final black square that I will mention here is of course the 1915 painting by Kazimir Malevich, described by Philip Shaw as ‘the slab of black paint that dominates the canvas,’ and which ‘works as a grand refusal.’ Perhaps the black square/page is an anomaly in the history of image making and particularly illustration as it is an attempt to communicate through a rejection of communication. It can however be said to link the texts in which it appears in a similar manner to the other images discussed here.

Can an image such as the black square really be said to both represent a refusal of narrative and be nomadic in the terms I am discussing in this paper? Considering the black page I began to wonder if nomadic illustrations really are moving at all. What if rather than being nomads wandering from context to context, these illustrations are nodes gathering narratives to them? In an essay called ‘Information design, emergent culture and experimental form in the novel’, Steve Tomasola describes research by Norm White and Rick Rosenfeld into co-defenders in the St. Louis crime records. The presentation of data that the researchers came up with linked offenders according to the crimes they had committed together, ‘by representing the crimes as a social network, their model revealed a previously invisible story: the identity of what might be called criminal hubs, nodes and spokes.’ (2012:446). A similar diagram might be drawn to represent the nomadic illustrations and the (usually hidden) connections they create between particular narratives. These networks are not new, but web browsers allow their presence to be exposed and utilised creatively. The networks I am describing are interesting precisely because they are limited and they can be mapped (and are therefore not rhizomes).

David Ciccorico writes in his essay ‘Networked fiction’ that, ‘digital fiction marks the emergence of a distinctly new narrative poetics – namely a poetics of the link and the node.’ (2012:469). If theses nodes are images, then this suggests and exciting role for illustration within the realm of digital (or non digital) fiction as an ‘organisin principle’. Ciccorico goes on to describe nodes as, ‘self contained semantic entities, meaningful both in isolation and in the network of which they are a part.’ This description of the node in digital fiction also functions as a description of the role of the nomadic illustration (although it is arguable that not all of the images discusse here are meaningful in isolation). The use of images to link and therefore comment on the shared properties of narrative opens up possibilities for illustrators; there is the potential to create online works in which narratives are connected by single images, something that the illustrator might choose to reveal or hold back. An illustrator might create an illustration with the intention that it should be nomadic and then observe and record the narratives it gathers to it as it progresses online (or offline, or across both). An illustrator might choose to include the same image in every text that they illustrate over the entire course of their career creating a node around which the texts would gather.

So, are nomadic illustrations moving or still? Images move or wander online when they are picked up and reused – dragged, dropped and downloaded. But once these images are in place in their multiple contexts they become nodes connecting these contexts and the narratives they contain (Figure 7). These connections remain largely hidden, in non-digital media they may be discovered and exposed by researchers but in the online space they are documented and may be revealed in an instant. It seems that it is very rare for a moving image to be used to say something wholly new in its new context. Susan Sontag discusses how easily the caption glove slides on and off in relation to the photographic image (1977: 109), but it seems that one of the things that causes an image to move is the ideas that become attached to it (as with the O’Keeffe mandala and the idea that Georgia O’Keeffe painted vaginas).

My final suggestion with regard to the necessary qualities or structures of nomadic images is their stillness. This is quite difficult to argue as it is based on a subjective judgement of what might make an image still. Here, I would define a still image as one in which a narrative event is not in the process of occurring. With the exception of the running man, many of the images discussed in this paper do not strongly imply a subsequent narrative event. In the case of the running man, the subsequent event implied would not radically alter the meaning (or aesthetic) of the image. He is running away from the camera, not, for example, out of the shot. The images discussed here could be said to be narratively static. Paradoxically, nomadic illustrations might move precisely because they are still.

Footnotes:

1 For a detailed discussion of all of the images in the G.G.I.D blog please my Ph.D thesis A Taxonomy of Deception.

2 https://www.facebook.com/pages/Free-AMINA/597130016982031?fref=ts

Accessed 21 st June 2015

3 http://www.mandalas.com/mandala/htdocs/FlowerGallery/Georgia_O%27Keefe.php

Accessed 21 st June 2015

4 http://colleendown.blogspot.co.uk/2011_05_01_archive.html target="_blank">blogspot.co.uk/2011_05_01_archive.html

Accessed 21 st June 2015

5 http://art160sxu.blogspot.co.uk/2010/04/flowers.html

Accessed 21 st June 2015

6 https://clarafications.wordpress.com/2009/12/14/georgia-okeefe-painted-vaginas/

Accessed 21 st June 2015

7 http://colleendown.blogspot.co.uk/2011_05_01_archive.html

Accessed 21 st June 2015

8 http://imgur.com/M1eQm

Accessed 21 st June 2015

9

10 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ocbdgIfLLAw

Accessed 21 st June 2015

10 For example, photographs by William Eggleston appear on the covers of the 2001 edition of In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

published by Vintage, the 2009 edition of Faithless by Joyce Carol Oates published by Harpercollins and on the 2013 cover of Mo said she was Quirky by James Kelman published by Penguin.

11 A Google search shows that this image has in fact become a meme spawning a Sesame Street version in which Kermit is on the slab and another version in which all of the faces have been replaced by emoticons.

References:

Addley, Esther (2011) ‘Arab spring: A gay girl in Damascus - or a cynical hoax?:

Credibility of Syria's lesbian blogger thrown into doubt by fake pictures and evasive,

secretive behaviour’, The Guardian, 10 June, 20

– (2011) ‘Syrian Lesbian Blogger is Revealed conclusively to be a married man’ The

Guardian, 13 June

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jun/13/syrian-lesbian-blogger-tom-

macmaster

Accessed 13 th February 2014

Bal, Mieke (2009) Narratology; Introduction to the Theory of Narrative (Third

Edition), Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press

Barthes, Roland ([1977] 1982) Image, Music, Text London: Fontana

– ([1980]2000) Camera Lucida London: Vintage

Ciccorico, David (2012) ‘Networked Fiction’ in: Bray, J, Gibbons, A, Mchale, B eds.

(2012) The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature, London, New York:

Routledge

Dawkins, Richard ([1976]2006) The Selfish Gene, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Dyer, Geoff (2006) The Ongoing Moment, London: Abacus

Eco, Umberto (1989) The Open Work

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press

Elkins, James (2013-2014) Writing with images

http://writingwithimages.com

Accessed 18 th June 2015

Eugenides, Geoffrey ([1993] 2002) The Virgin Suicides, London: Bloomsbury

Glieck, James (2011) ‘What defines a meme?’ Smithsonian Magazine (Online), May

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/what-defines-a-meme-1904778/?no-ist

Accessed 18 th June 2015

Goldsmith, Kenneth (2013) Uncreative Writing, New York: Columbia University

Press

Gombrich, Ernst Hans (1960) Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of

Pictorial Representation, 6th ed, London: Phaidon, (2002)

Hughes, Sarah Anne (2011) ‘Hurricane Irene: ‘Photo’ of shark swimming in street is

fake’ in The Washinton Post (Online), 26 th Aug

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/blogpost/post/hurricane-irene-photo-of-shark-

swimming-in-street-is-fake/2011/08/26/gIQABHAvfJ_blog.html

Accessed 20 th June 2015

Horspool, David (2012) ‘Cover Versions’ in The TLS Blog, 26 th March

http://timescolumns.typepad.com/stothard/2012/03/cover-versions.html%20

Accessed 21 st June 2015

Lichtig, Toby (2013) ‘Cover Versions Redux’ in The TLS Blog, 1 st March

http://timescolumns.typepad.com/stothard/2013/03/cover-versions-redux.html

Accessed 21 st June 2015

MacMaster, Tom (2011) A Gay Girl in Damascus

http://www.minalhajratwala.com/wp-

content/uploads/2011/06/damascusgaygirl.blogspot.com_.zip

Accessed 10 th February 2014

Marsh, Katherine (2011) ‘A Gay Girl in Damascus becomes a heroine of the Syrian

revolt’ The Guardian [Online], 6 June

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/may/06/gay-girl-damascus-syria-blog

Accessed 20 th June 2015

Mitchell, William J (1992) The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-

Photographic Era, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press

O’Hagan, Sean (2011) ‘Out of the Ordinary’ The Guardian, London: 25 th July

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2004/jul/25/photography1

Accessed 20 th June 2015

– (2006) ‘Will the real Marcia please stand up’ The Guardian, London: 23 rd April

http://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2006/apr/23/features.review17

Accessed 20 th June 2015

Plascencia, Salvador (2007) People of Paper, London: Bloomsbury

Randhawa, Kiran (2011)'Kidnapped' blogger stole my identity, says Londoner’

Evening Standard London: 9th June, p. 9

Rawlings Tomas (2011) ‘Deus Ex: Medical Revolution’, Wellcome Trust Blog

20 th Sept

http://blog.wellcome.ac.uk/2011/09/20/deus-ex-medical-revolution/

Accessed 20 th June 2015

Sebald, W.G. (2002) Rings of Saturn, London: Vintage

Shaw, Philip (No Date) ‘Kasimir Malevich’s Black Square’, Tate

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/the-sublime/philip-shaw-kasimir-

malevichs-black-square-r1141459

Accessed 20 th June 2015

Smith, Ali (2005) The Accidental, London: Hamish Hamilton

Sontag, Susan (1977) On Photography, London: Penguin

Tartt, Donna (2013) The Goldfinch, London: Abacus

Tomasola, Steve (2012) ‘Information design, emergent culture and experimental

form’ in: Bray, J, Gibbons, A, Mchale, B eds. (2012) The Routledge Companion to

Experimental Literature, London, New York: Routledge

Trettien, Whitney Anne (2012) ‘Tristram Shandy and the Art of Black Mourning

Pages’ in Diapsalmata, 17 th September

http://blog.whitneyannetrettien.com/2012/09/tristram-shandy-art-of-black-

mourning.html

Accessed 22 nd June 2015

(2010) ‘Huge shark-filled aquarium in Dubai cracks open’ in BBC News (Online), 25 th

Feb

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/8536415.stm

Accessed 20 th June 2015

(2010) ‘Don’t you walk away from me with your hat on!’, The Fiction Desk, 7 th Sept

http://www.thefictiondesk.com/blog/dont-you-walk-away-from-me-with-your-hat-on/

Accessed 20 th June 2015

(2012) ‘Your news: editors picks’ in CBC News, 1 st June

http://yournews.cbc.ca/mediadetail/6647293-Union%20Station%20Flood%20-

%20June%201st?groupId=11825&uid=&sort=upload%20DESC&offset=2

Accessed 20 th June 2015

(2012) ‘Sharks in Union Station image goes viral as Kuwait Shark tank collapse [sic]’

in Yahoo News (Canada): Daily Buzz, 18 th June

https://ca.news.yahoo.com/blogs/daily-buzz/sharks-flooded-union-station-image-

goes-viral-kuwait-204251203.html

Accessed 20 th June 2015

(2012) ‘Shark Tank Breaks in China, Floods Shanghai Mall’ in The Huffington Post,

26 th Dec

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/12/27/shark-tank-breaks-china-

video_n_2369967.html

Accessed 20 th June 2015

(2012) ‘Hurricaine Sandy Photographs’ in Snopes, 26 th Nov

http://www.snopes.com/photos/natural/sandy.asp

Accessed 20 th June 2015